SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

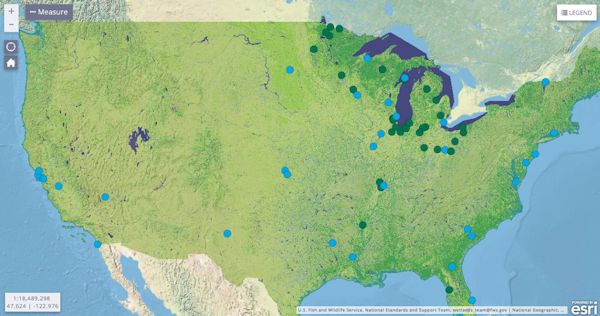

| Screenshot of the National Wetlands Inventory Mapper, with wetlands data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Image: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Click to view interactive maps. Click to enlarge. |

TipSheet: Track Wetlands Stories with National Inventory Tool

Wetlands are news almost anywhere you look. Environmental journalists can zero in on local and regional wetlands stories using one key data tool — and the proverbial nose for news.

An epic fight over wetlands protection is sparking a legal showdown over which waters are protected from pollution, with the “Waters of the United States” rulemaking (subscription required) at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The benches have been cleared, with farmers and developers facing off against environmentalists as EPA tries to make a rule that will certainly end up in court (again).

Section 404 of the 1972 Clean Water Act has been the nation’s main mechanism for protecting wetlands for decades. It has been law, and it has been controversial, for all that time. But don’t overlook the really important local wetland and small-stream stories because of the big national issues.

An often-overlooked tool in finding these stores is the National Wetlands Inventory. It’s far from perfect or complete — but it’s online, searchable, downloadable, map-based and Google-friendly. Once you determine what are the important wetlands near you, you can start the real reporting.

They say when your only tool is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. This often holds for data journalism tools, too. Use the National Wetlands Inventory. But you may also want to borrow a pair of chest waders, go on a bird walk, borrow a canoe, dig up court records and spend hours drinking coffee with frustrated land owners.

The backstory

Under Section 404, a person must get a permit before dredging or filling waters of the United States. While this section of the law hearkens back to 19th century law promoting navigation, it evolved into a permit program for disturbance of wetlands. The permit program is overseen jointly by the EPA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Dredging and filling are two major ways wetlands are disturbed, but disturbance happens for many reasons — farming and land development are two of the most common. Flat, well-drained land can make farms more productive. And developers can acquire a valuable asset by creating lands where swamps once stood.

Both groups often view wetlands protection as a taking of something that belongs to them. But Section 404 eases the pinch in many ways. Permit-holders can offset wetland destruction by “mitigation,” or creating wetlands nearby. There are many exemptions for normal farming. The law allows for “general permits,” meaning broad, generic permissions with no paperwork.

But Supreme Court decisions in 2001 and 2006 upset long-established interpretations of the 1972 law … without establishing a practical alternative. The Obama EPA in 2015 tried to fill this vacuum with its “Waters of the United States,” or WOTUS rule. The Trump administration, once in office, embarked on a new rulemaking trying to replace it with one applying CWA protections to far fewer U.S. waters. That rule has not yet been finalized.

Why it matters

Wetlands are of tremendous value to people (and to nature) as an environmental resource. They are habitat for wildlife, fish, insects and important plants. They are carbon sinks. They help control floods, coastal storm damage and sea level rise. They help purify water. They even create soil. Plus they are beautiful places to paint, watch birds or paddle a canoe.

The loss of wetlands is a serious problem. Huge amounts of wetlands have been lost since the settling of North America by Europeans. The losses continue today.

Meanwhile, here are some cool things about the National Wetlands Inventory:

- It is run by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, but relies on lots of data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

- The data in it are essentially geographic, or GIS, data.

- You can download the whole data set.

- A record can contain up to eight layers, which includes historical information.

- You can look at the data by watershed.

- The website displays data in map form. Here’s a video on how to use the mapper.

- The inventory regularly generates reports on wetlands status and trends by various meaningful geographic categories.

- The data can be viewed via KML, or keyhole markup language, files. That makes it compatible with ArcGIS Explorer and Google Earth.

Story ideas

- Start with a major land or real estate development project of local interest. What permits does it need? Where do they stand?

- Or start with a body of water that’s important to your area — like a beloved estuary used for recreation, boating and fishing. What threatens its connected wetlands?

- What do your local planning and zoning regulations and agencies say about wetlands conservation?

- Does your area have a stormwater management plan or plans? What is the connection with wetlands?

Other reporting resources

Some potential sources for wetlands stories:

- Local real estate developers, or the National Association of Home Builders, for general industry positions.

- Local farm groups, or the American Farm Bureau Federation.

- Association of State Floodplain Managers, good on flood-related wetlands issues.

- Association of State Wetland Managers, a pro-wetland group whose partners include more than just state officials.

- Society of Wetland Scientists, includes scientists as members and publishes a journal.

- Wetlands Institute, a membership-based nonprofit that advocates for wetlands preservation.

- Local environmental groups, which are often involved in wetlands preservation.

- Past SEJournal content, including TipSheets on wetlands mitgation and wetlands permitting, and a Beat Basics explainer on WOTUS.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 4, No. 18. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement