SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

|

| The author, hiking while pregnant through Glen Affric in Scotland, one of the locations featured in her book. |

Freelance Files: From Reporter to Author — How I Published My First Book

By Sophie Yeo

By the time I signed the contract for writing my first book, I had been a journalist for seven years, four of which I had been freelancing.

I had always wanted to write a book, but the process of finding a publisher seemed daunting; I didn’t know where to begin. The pressure of making enough money to live meant that I focused my efforts on writing regular articles. Finding the time to write a book proposal and then a book, with a presumably minimal advance, seemed impossible.

I had always had a vague idea

of what I would write about if

I ever did find the time to write

a book: environmental history.

But I had always had a vague idea of what I would write about if I ever did find the time to write a book: environmental history. I had long been fascinated by how scientists use historical records to reconstruct the ancient landscape and the lives of the creatures that occupied it.

This idea coexisted with another ambition: to set up an online publication devoted to in-depth journalism on nature in Britain. I had spent a few years living and writing in the United States, where there seemed to be greater scope for long-form journalism than in England, particularly where the natural world was concerned.

This plan was easier to execute. I was accountable only to myself. I could start small and give up if it didn’t work out. When my other freelance work dried up at the start of the pandemic, I decided to devote a couple of weeks to making this dream a reality. Inkcap Journal was born.

The website was a success. Growing subscriber numbers meant I finally had a small but regular income. It also boosted my own reputation. Within a few months, I had a publisher approach me asking whether I had ever considered writing a book. A few weeks later, another publisher asked me the same question.

With the stability and security of Inkcap Journal, the notion no longer seemed so insane. I hastily put together a book proposal: a chapter-by-chapter outline of what I thought I might write about, which ultimately bore little resemblance to the final project. And I dashed off some speculative emails to agents that I knew had represented authors writing within the same genre.

Soon after, I had representation, a book deal and a deadline of 18 months to submit 80,000 words.

Writing the book — from disorienting to familiar

As a journalist, I had mostly written articles of between 800 and 3,000 words. There is something disorientating about multiplying that number by a hundred.

|

My experience as a freelancer did not prepare me for becoming an author. With shorter articles, I often started with a specific hook — a project, a paper, a policy — that I knew would guide the direction of the piece. The structure was often self-evident from the start. Writing a book, I felt at sea.

The book was to be about the history of the natural world and how understanding the past can inform nature conservation today. The subject involved a lot of complex science and nuanced debate.

I started by doing a lot of reading and research. I needed to get to grips with the topic, but also to figure out how I was going to divide this amorphous ball of knowledge into discrete chapters and stories. I also expended a lot of mental energy on ignoring the sense of rising panic at the absence of any words on the page.

Once I had figured out the structure, the task began to feel more familiar. I set up interviews, arranged visits and undertook more specialized research. The 80,000 words began to separate into manageable chunks.

This process was somewhat iterative: I shifted sections around and discovered new and better case studies as I deepened my research. By the time I had a realistic blueprint, however, I found I was halfway through my 18-month timeline. Not long after that, I discovered I was pregnant.

My panic intensified. There’s no rulebook on pregnancy while writing a book. Contracted to a publisher, you exist in the vague space between employment and independence. I contacted my editor and got an extension. My draft and my baby were now due at the same time.

The publishing process — anxiety amplified

I didn’t make that deadline, either, but I did eventually submit a first draft when my baby was around eight months old.

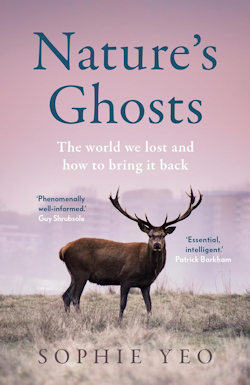

My resulting book, “Nature’s Ghosts: The World We Lost and How To Bring It Back” is published by HarperNorth, an imprint of HarperCollins focusing on writers based in the north of England. Beyond asking for extensions to my deadline, I’d had relatively little interaction with them until that point. Now, my work was in their hands.

During my years of freelancing, I had worked with many editors at a range of publications, so I felt like I had a good idea of what to expect. I was wrong. The world of publishing felt alien to me. As an outsider, I didn’t understand the norms, the jargon, the structure, the process. Nor was this information particularly easy to find.

I felt like I had thrown my book into

a black hole. All I could do was wait,

worry and wonder what it would

look like when it reemerged.

For a long time, I felt like I had thrown my book into a black hole. All I could do was wait, worry and wonder what it would look like when it reemerged.

The experience was unlike anything I had experienced in the world of journalism, which tends to move swiftly, even at its slowest. Those months of waiting were among the most stressful of my career to date.

The usual anxieties of writing and publishing become magnified when you have invested three years — and a large part of your soul — in a project.

Talking to other published writers was the best salve; it is easy to feel like a cog in a machine, and sharing stories and experiences with others made me feel less alone and gave me a barometer against which to judge my own experience.

I have yet to meet another writer who is unwilling to lend an ear or impart advice: It is often the only way to navigate these unfamiliar waters.

A real book — the broader lessons

Writing and publishing “Nature’s Ghosts” was wonderful, demanding, rewarding, fascinating, frustrating, exciting. My journey from freelancer to published author has felt a little unorthodox. However, I think there are some broader lessons that can be drawn from it.

Firstly, make sure you are in a position to afford it. Without the stability of Inkcap Journal, “Nature’s Ghosts” would have remained an impossible dream.

Writing my book has been all-consuming, often leaving little time or brainspace for pitching and writing for other publications. I hate to think what my hourly rate has been, based upon my advance, or the income I have foregone in the projects I have turned down. I do my best to ignore the internal voice that calls this my expensive hobby.

Secondly, do your research. The best information probably doesn’t appear online. Talk to other writers. Ask questions. Publishing a book is not like publishing an article. The writing takes more from you — intellectually, emotionally, logistically — and the business behind the final product works differently. Understand what you are getting into.

Finally, make sure you are utterly passionate about your subject. “Nature’s Ghosts” has been my life for four years. Sometimes, I have found myself so thrilled by a study on extinct megafauna that I can barely think. I have mused upon old-growth pinewoods while bouncing on a birthing ball and listened back to interviews about medieval farms while pushing the pram ad nauseam around the park.

The historical landscape has become my world; I am not sure I’ll ever fully return to the present.

Sophie Yeo is a writer and journalist based in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England. She has written about nature and climate change for publications including The Washington Post, The Guardian and BBC Future. She is the author of “Nature’s Ghosts: The World We Lost and How To Bring It Back,” which was published in the United Kingdom on May 23, 2024 and will be available in the United States on July 30 (pre-order here). She is also the founder and editor of Inkcap Journal, an online publication focusing on conservation in Britain, which won the Press Gazette Newsletter of the Year award in 2022.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 9, No. 23. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement