SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

BookShelf: A Castoff Bumper Leads to a Literary ‘Autobiography’ of Plastic

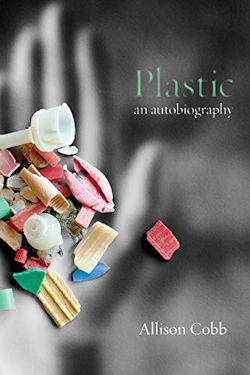

“Plastic: An Autobiography”

By Allison Cobb

Nightboat Books, $17.95

Reviewed by Nano Riley

|

The ubiquitous nature of plastic dawned on Allison Cobb after she found a plastic automobile bumper one day in her yard, detritus from a Honda Odyssey.

Cobb, who spent 20 years writing for the Environmental Defense Fund, recalled how she retrieved it, placed it in her office and thought about it on and off for about a decade.

Ultimately, the castoff bumper became the inspiration for her book, “Plastic: An Autobiography,” which traces how she related plastics to her life.

That old bumper wasn’t the only piece of plastic Cobb found on her daily dog walks, but it became the centerpiece of her collection. In her book, she wrote about how it stuck out most in her mind and got her thinking about plastics in general, prompting philosophical musings relating to the material’s longevity.

Cobb wants readers to know that even in a world of rampant consumerism, plastic never really goes away: It just shifts from landfills to the ocean and beyond on its perpetual journey. It’s an eternal pandemic.

A corporate boon

Plastic is, for her, also a reflection of corporate greed. It’s been a boon to corporate profits, as manufacturers race to create every useful object from the substance.

As Cobb reported, its desirability is not by chance, either. In 1945, a DuPont executive anticipated a buying surge after World War II ended, telling his marketing team that “Americans are never satisfied.” He saw ways for increased use of plastic to fill that demand.

Post-WWII plastic was the desired material for an unending array of products made from easily available sources, Cobb wrote.

Literary references pervade this book, each

related to plastic in some way, as Cobb

travels through history to reveal connections.

She noted that “seemingly endless reservoirs of dead plants and animals underlying Earth — plastic transmutes death into eternal life.” Fossilized materials pressed by the Earth for millions of years yielded not only gas for fuel, but oil to create plastic.

The greenwashing of plastic followed. Even during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Cobb recounts how plastic manufacturers lobbied the Trump administration to overturn bans on single-use plastics, touting it as “the most sanitary choice,” despite proof that plastic retained viable viruses longer than cardboard or cloth.

Intertwining narratives across time

Cobb, who is also a poet, channels her literary talents in a variety of styles, intertwining narratives across time. Literary references pervade this book, each related to plastic in some way, as Cobb travels through history to reveal connections.

This is not a linear tale, not one you’d read at once. It’s better to read a few chapters at a time. Each chapter is short, and not necessarily related.

When an albatross chick died in 2006, its stomach choked by plastic, including a piece identified from a WWII plane, Cobb used the moment to trace the piece to a particular squadron and a pilot who was lost, while the plastic lived on.

Elsewhere, she considered during a trip to Hawaii’s Kamilo Point, a beach where currents deposit sea trash, how the five great ocean gyres, a boon to centuries of global sailors, are now swirling with plastic.

Hope amid a grim picture

Cobb noted that while Asian countries release the most ocean garbage, according to a 2015 study in Science, that debris is from nations worldwide that export trash for recycling.

She wrote how plastic manufacturers bamboozle school children into recycling competitions, creating a distraction while they make more. The result has been a never-ending stream, leaving no corner of Earth untouched.

Cobb also cited communities of color that have been

the site of plastic plants for decades, only to be plagued

by illnesses brought on by polluted air and water.

Cobb also cited communities of color that have been the site of plastic plants for decades, only to be plagued by illnesses brought on by polluted air and water.

But Cobb, well-versed in the realm of environmentalism from her experiences in writing for EDF, noted in her book how the daily deluge of negative information can weigh heavily on one’s mind, as environmental journalists are keenly aware.

So despite the grim picture, she finds hope in those, like residents of communities of color, who are rising up to fight back, intent on saving future generations.

In the end, the book brings us back humorously to her bumper. Cobb recounts when she traveled with it to a Honda factory in Alabama in an attempt to recycle it. There she was told: “We can’t accept that, it's yours.”

Nano Riley is a member of the Society of Environmental Journalists, a journalist, an environmental historian and author of the 2003 book, “Florida's Farmworkers in the 21st Century.”

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 7, No. 13. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement