SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

|

| Houston emerged as what one expert called one of the most pro-growth and least regulated cities in the Western world. Above, a view of the Houston Ship Channel, packed with petrochemical processing plants and subject of decades-old struggles over toxic air emissions. Photo: Roy Luck, Flickr Creative Commons. Click to enlarge. |

Special TipSheet: Deep in the Heart of Complexity … Or, the View From Texas

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story is one in a series of special reports from SEJournal that looks ahead to key issues in the coming year. Visit the full “2022 Journalists’ Guide to Energy & Environment” special report for more.

By Greg Harman

Houston may not have been built entirely by oil and gas, but its landscape today would not be recognizable without the economic and political forces that for more than a century pinned their growth on cornering crude and steering it to the global market.

Those oil and gas ties are inescapable, almost no matter where you go within the state's ten ecoregions. “Every environmental story [in Texas] seems to start and end there,” said Dallas-based independent journalist Amal Ahmed.

The city burst into its current shape in the post-World War II years, becoming what Rice University's Stephen Klineberg called one of the most pro-growth and least regulated in the Western world. Today, the Houston Ship Channel, like Louisiana's “Cancer Alley,” is chock full of petrochemical processing plants and decades-old struggles over toxic air emissions and explosions.

Houston is now a city in the midst of a radical

recreation, buffeted by demographic shifts,

rising concerns with racial and economic justice,

and an overdue but growing climate response.

But the sprawling wealth gap that emerged, as well as the destabilizing oil bust of the 1980s, shook the city's confidence. And Houston is now a city in the midst of a radical recreation, buffeted by demographic shifts, rising concerns with racial and economic justice, and an overdue but growing climate response.

While the legacy of environmental racism here has been long understood (the “father of environmental justice” Robert Bullard served as a revered dean at Houston’s Texas Southern University), the killing by Minneapolis police in 2020 of George Floyd — who hailed originally from Houston's Third Ward — forced even the city's mainstream environmental organizations to prioritize antiracism and equity in ways they had long avoided, according to Rachel Powers, director of the 50-year-old Citizens Environmental Coalition, or CEC.

But if the world understands the environmental justice realities of Houston so well (well enough that they are visible from space, as one writer emphasized in Environmental Health News recently), local activist-journalist Bryan Parras still wishes “they could see it from the West Side.” In other words, there’s a long way to go yet.

So as journalists from around the country and beyond prepare to descend on Bayou City at the end of March for the Society of Environmental Journalists' 31st annual conference, many undoubtedly will be forced to reexamine long-held ideas about Houston, and Texas generally, with the reality they meet on the ground.

To help prepare conference attendees (particularly non-Texans), I surveyed nearly a dozen journalists, activists and academics about what reporters should know about Houston and Texas entering 2022. Some had resources to share and stories to recommend. Others wanted to offer advice about reporting those stories effectively.

[And since space is limited here, I’ll also be making available longer supplementary video statements from many of those who spoke with me at my own website, Deceleration.news. There’s more, too, on the SEJ conference co-chairs’ welcome letter and “About Houston” resource page].

We believe! We believe!

So, welcome to Texas, where contrary to what some might expect, residents do believe global warming is happening. In fact, according to a recent survey from the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, they believe it by a tick higher than the national average (72% vs. 71%) and are worried about it at the same level (63%).

In Houston itself, residents have grown increasingly concerned over the last decade. Those who feel global warming is a “very serious problem” have grown from 38.5% in 2010 to 51.1% in 2020, according to Klineberg, who has led Rice's Kinder Institute for Urban Research for 40 years.

Meanwhile, those understanding human activities are to blame and not, specifically, “normal climate cycles,” rose during the same period from 38.5% to 69.9%.

Resource: Check out the Kinder Institute report, “The Fortieth Year of the Kinder Houston Area Survey: Into the Post-Pandemic Future.”

Climate plans and purchase agreements

Major Texas metros, including Houston, have passed a string of climate plans in recent years. Houston's 2020 climate plan was matched by a 100% renewable energy purchase agreement, making it one of the largest governmental purchasers of clean energy in the United States. It reached 99.8% renewable energy last year, purchasing more than 1 billion kilowatt hours of wind and solar, according to the EPA.

Meanwhile, Dallas hasn't taken strong action on the components of its plan, according to Fort Worth Report's Haley Samsel, but has been dutifully purchasing 100% renewable energy sources for city operations since 2015.

|

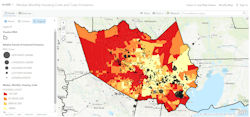

| An interactive map of Houston housing costs and toxic emissions. Image: Air Alliance Houston. Click to enlarge. |

In San Antonio, a proposal from within the city’s climate committees to focus on city-owned CPS Energy’s massive emissions has proved strangely controversial.

Although the Texas Legislature has made it hard for cities to limit fracking (and illegal to exclude gas from new buildings), there are still a lot of tools in municipal tool belts.

“Will local governments take action where state leaders won’t? That’s the question that will dominate environmental conversations in 2022,” Samsel wrote us shortly after filing a story about a fracking permit denied in Arlington, Texas. It’s the first, she said, since the Texas Legislature banned fracking bans in 2015. Expect the legal debates to follow.

The new Houston

“Elections matter. Voting rights matter,” said the CEC’s Powers. She credited the evolving climate plan of Harris County, of which Houston is county seat, in part to the recent election of County Judge Lina Hidalgo, its first woman in the position — and the first Democrat to hold the seat in almost 30 years.

The climate planning process in the county “is not something that would have been possible just four years ago,” Power said. “You couldn't say 'climate' if you were in Harris County.”;

Klineberg also notes the shift: “By the time the [city’s] Bayou Greenways initiative is completed at the end of next year, Houston will be one of the greenest cities in America. … It's a city self-consciously aware that its strategies for economic prosperity now require far greater attention to quality of life issues, to environmental protection, to physical beauty.”

Resource: The 50-year-old CEC is actively digitizing its considerable newsletter archives, sure to be a gem for environment reporters and researchers for years to come.

Subverting the 'white gaze'

Ahmed said that many of her leads come out of listening to public comment sessions or dropping in on community webinars. But to report effectively on communities she doesn’t have personal intimate knowledge of, she frequently relies on local organizations to find interview subjects.

“I do not like the concept of knocking on doors just to try to find someone,” Ahmed said. “My approach is to find the groups working in the community first, [then] I'll ask those groups once I've established that trust.” Adds Ahmed: "I know other [reporters] may feel differently. … But to me, any other way feels extractive and intrusive.”

Parras supported that approach. “There's still anger and frustration when there are mostly white journalists telling people of color stories [in Houston], or folks not from a particular area framing something in a way that doesn't make sense,” he said. “Thinking of media as white gazing, like a point of view.”

When I asked the clean-air advocates at Air Alliance Houston what they want journalists to understand about the city, they also directed focus to frontline communities. "What I’d personally want journalists to know about Houston,” said Jennifer Hadayia, the alliance’s executive director, “is how engaged and committed community residents, usually of color and lower-income, are working to protect their health from the cumulative impacts of nearby air pollution sources.”

Resource: Air Alliance's sizable suite of air toxics data maps is worth exploring. Also be on the watch for even more maps in 2022, I'm told, including upgrades to the group's tracking tool for air permit notifications.

A private property (and power grid) state

When the United States absorbed the Republic of Texas in 1845, it took on all of Texas' debts while allowing the continuation of slavery (a hard demand of the short-lived republic, even as the nation lurched toward civil war) and full control over its public lands. That last fact is why our state is more than 95% privately owned.

|

| Linemen work to restore power Feb. 17, 2021, after a major winter storm. Photo: Jonathan Cutrer, Flickr Creative Commons. Click to enlarge. |

Beyond the continuing toll this takes on Native peoples long excluded from their sacred sites, it makes any story about opportunities to incentivize land conservation with rural property owners (say, Build Back Better, ranchland and the potential for carbon sequestration payouts) an important one.

The same resistance to federal regulatory influence that formed the state helps explain why the state has an independent power grid (as opposed to a system integrated into the massive Eastern and Western U.S. grids we are sandwiched between).

That isolation didn't serve us well when a major winter storm hit a year ago, killing hundreds and leaving the grid less than five minutes from total failure.

Nearly one year later, gas companies remain woefully unprepared, with more than 1 gigawatt of gas facilities unable to power up during 2022's first freeze.

Don't just fix it — connect the grid

Campaigns around “fixing” the grid, for example by forcing gas companies to weatherize, are plentiful. What hasn't materialized is a dedicated campaign to “connect the grid” to the rest of the country.

“You can imagine in an age of better leadership we would be doing that right now,” said Brendan Gibbons, who covered the environment and energy beat for the San Antonio Report (and, earlier, the San Antonio Express-News) before joining the Greater Edwards Aquifer Alliance last month to protect and preserve area watersheds.

Unfortunately, that hasn't been the conversation, Gibbons said. Rather, the reality on the ground has meant those with the means scrambling for home generators. “And that's just a terrible model. It's like civilization backsliding. I find that a pretty potent example of an ‘Are we going to have a society together or not?’ type of question.”

Meanwhile, joining the other grids would also bring benefits for human security and the energy sector, easing the problem of stranded solar and wind, he added. Roughly 28% of all wind-generated electricity in 2019 was found to be stranded, for example, because of transmission constraints and other issues.

Reforming energy regulators

Two activists I spoke with summoned the birth of Commission Shift a year ago as one of the most significant events on their radar. Commission Shift is a new nonprofit dedicated to bringing ethics reform to the Railroad Commission of Texas, or RRC, which regulates the state’s oil and gas industry.

In the space of a single year, Commission Shift, led by Laredo resident Virginia Palacios, has made considerable waves publishing a series of reports profiling the RRC commissioners based largely on their financial disclosure statements.

“We found that more than two-thirds of the commissioners' campaign funding comes from the oil and gas industry, the same companies they are supposed to be overseeing,” said Palacios. To be clear, the massive donations have not stopped these same commissioners from voting regularly on new permits for their contributors, which is clearly wrong and may not be legal (yes, even in Texas).

“When I look at the statute and I look at the recusal policy that is on the books, I don't think it does allow them to vote on those issues,” she added. “But I think the problem is the state attorney general is not enforcing the rule and the commissioners are not following it.”

Consider the Houston Chronicle's editorial board convinced. In a November 2021 editorial, it cited Shift's work while calling for two of the three commissioners to resign.

Resource: Commission Shift’s “Captive Agency" report series details the financial disclosures of the three RRC commissioners. With nearly $5 billion in federal funds coming available to states for plugging abandoned oil wells, watch also for a new Commission Shift report on orphaned wells later this month. Also see an overview of the problem in the SEJournal’s Jan. 19, 2022, TipSheet.

'The buildout'

The U.S. Energy Information Administration estimates that more than 40% of U.S. oil and gas reserves are in Texas. But the state also has nearly as much wind power as the next four top wind-producing states — Iowa, Oklahoma, California and Kansas — combined. And while California dominates in solar, Texas is a strong second when measured against the rest of the pack. (And battery development is advancing at a decent clip.)

But the most visible energy movement is by far with what Catholic Sister and anti-fracking activist Elizabeth Riebschlaeger called “the buildout,” a rush to the Gulf Coast to reach the global market.

Remember when ‘Drill, Baby! Drill!’ was about

domestic energy security? The fracking boom,

phase 2, is about pipelines and ports to

take Texas fracked gas to world markets.

Remember the 2008 national presidential campaign debates, when “Drill, Baby! Drill!” was about domestic energy security? The fracking boom, phase 2, is about pipelines and ports to take Texas fracked gas to world markets.

Included in the buildout have been petrochemical plants like the Saudi-Exxon joint ethylene venture expected to come online in Corpus Christi (subscription required) this year. But it's not going easily for the companies. Earlier this month, news broke of another significant LNG delay.

Nurdle patrol, assemble!

Maybe you've already had your moment reporting the largest-ever Clean Water Act settlement flowing out of Waterkeeper v. Formosa. Last December’s settlement for $50 million — roughly $1.66 for every tiny plastic pellet, or “nurdle,” produced by the plastics giant and fished out of the Gulf of Mexico by the plaintiffs — has already generated new proactive efforts.

As Suzanne Freeman writes at the Corpus Christi Business News, a so-called Nurdle Patrol, based within the University of Texas Marine Science Institute but heavily reliant on citizen science, was quickly granted $1 million of that settlement to expand programs that collect and document the extent of plastics pollution.

Colonizing Mars … and the Rio Grande Valley?

NASA may have inspired the nation from Houston’s Johnson Space Center, but the selfie-era glamour of emerging space tourism has shifted focus to private space explorers in West Texas and in the Rio Grande Valley. And while Elon Musk may have his eye on Mars, it is important not to overlook the power of his very real colonial impulse as it’s being felt here on Earth.

Emma Guevara of the South Texas Environmental Justice Network entreats reporters writing about SpaceX to seriously consider what it means when Musk tweets about founding a new city called “Starbase” on land that has been inhabited, traveled, understood and loved for thousands of years in patterns of pre-existing relationship.

She argues that callous writing “actively contributes to our erasure so that a billionaire can lay claim to the land and use it to blow up rockets and pollute the beach.”

Resource: You may not agree with all of what Guevara lays out in the post, “What journalists should know before reporting on the SpaceX at Boca Chica Beach,” but it offers lots of healthy food for thought.

Let me leave this right here …

In one of his first acts in office, President Joe Biden put the border wall on ice. But in spite of his Jan. 20, 2021 proclamation and the subsequent cancellation of construction contracts in the Rio Grande Valley and Laredo sectors, something is going up outside the National Butterfly Center that looks suspiciously, er, wall-like.

They're calling it levee repair, but then anti-border-wall activists like Scott Nicol would like someone to explain those towering steel bollards on top.

Also, someone may want to check in on Mr. Goodbar, the endangered Mexican gray wolf who walked miles to get around a section of border wall.

Enjoy the late January look-ahead and the annual conference!

Greg Harman is an independent journalist and former community organizer who has written about environmental health and justice issues since the late 1990s. He has worked as a clean energy organizer for the Lone Star chapter of the Sierra Club and is a former editor of the San Antonio Current and former contributing editor at Texas Climate News. His work has appeared in places such as the Austin Chronicle, The Guardian, Indian Country Today, Yes! Magazine, Houston Press, VICE and the Texas Observer, among others. He is the founder and co-editor of Deceleration, an online journal of environmental news and analysis.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 7, No. 3. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement