SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

Feature

By ROGER ARCHIBALD

Long dormant EPA photojournalism project being rediscovered and revived

|

|

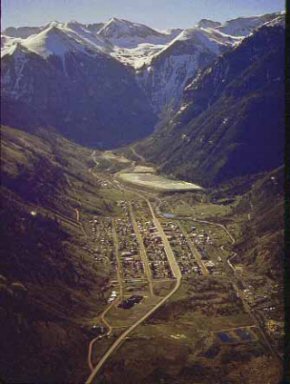

| BEFORE & AFTER: Documerica photographer Bill Gillette shot this aerial view of Telluride, CO (left) complete with lead, zinc, gold and silver processing mill settling pond (background) in May 1972, before it became a ski resort. By 2004, skiing was well established and the mining company was gone, but clear evidence of the former settling pond remained. BEFORE Photo: Bill Gillette, EPA-Documerica / NARA. AFTER Photo: © Roger Archibald. |

Jeremy Herliczek, a Michigan State University graduate student and photographer, was searching the internet in 2006 for a new project idea, using the terms “environmental” and “photo.” One result led him to a photo. He clicked on it. And soon one photo followed another. He had entered a world of vital images he didn’t even know existed. The feeling, he recalled, “was like finding the Ark of the Covenant in that wooden crate in the huge Government warehouse where it’s being stored at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark.”

Herliczek had discovered the lost treasure of Documerica, a photo archive that has lain dormant and largely invisible for nearly four decades. Born in the first year of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s existence, Documerica contains thousands of color photographs depicting a nation and its environmental problems in the early 1970s, the advent of the modern environmental movement in America. Documerica depicted strip mining, America’s car culture and the vast air pollution problems of a nation just coming to grips with some of its most important regulatory efforts.

Today, Documerica’s rediscovery is giving birth to another new and important photojournalism effort. The EPA has initiated a new project, a State of the Environment Photo Project, that could be dubbed Docuworld, inviting participants from all over, not just the United States, to submit their work. The new EPA effort includes Location Challenge, which seeks to have photographers replicate the same scenes depicted in the original Documerica photographs forty years ago.

Herliczek was so inspired by his accidental discovery of Documerica that he set about building a web site to promote Documerica, with helpful hints for journalists to ease access to the Archives. The Knight Center for Environmental Journalism at Michigan State University even financed a research trip he took to the National Archives to learn more about the collection.

It now hosts the site he developed at this link.

Herliczek was not alone in his surprise. In 2009, Jerry Simmons worked at the National Archives, as leader of the ‘Authority’ team that performs special cataloging functions, when he was assigned to clean up errors in the collection’s records. In Documerica, he expected to find old black and white photos; instead, “they were all in color, thousands of them.” In an effort to “piece together where they’d all come from,” Simmons worked his way “back through the contrail” they’d left in the Archives, as he puts it, to discover their source. When he found it, he was amazed that he’d never heard of the collection before, even while working under the same roof.

Simmons also embraced his discovery, writing a major feature for the Archives’ Prologue magazine about Documerica, contacting a number of its past photographers in the process. At the same time, he was instrumental in creating a Documerica presence on Flickr to which image files have been uploaded with much higher resolution than those available on the National Archives site (it’s much easier to navigate, too). And that’s not all — on his own time, Simmons has created a blog titled Daily Documerica where he publishes a different picture from the project every day or so, and a short story about it.

Of course, Documerica wasn’t the first time the federal government dispatched dozens of photographers into the country to make one vast multi-faceted portrait of American life. In the 1930s, the Farm Security Administration’s photographers created such famed iconic Depression-era imagery as Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother. Likewise, the goal of Project Documerica was to focus the talent and skill of a corps of the country’s top photojournalists on the state of the American environment in its broadest sense at a time that coincided with the modern environmental movement’s birth.

During the six years following the project’s launch in 1971, over a hundred different photographers participated at one time or another, hired as freelancers for assignments lasting up to thirty days. Although most worked within the regions where they lived, the collective set of images they produced spanned the entire country and in some cases reached abroad.

Within the project’s first year, an exhibition of some of the early work was mounted at Washington’s Corcoran Gallery, followed by a traveling set of exhibits sponsored by the Smithsonian that implied a promise of more to come. All told, while covering 164 separate assignments, project photographers shot over 80,000 photos; 22,000 were chosen to become part of the permanent Documerica collection. Like the earlier taxpayer-supported FSA photography, all selected pictures immediately entered the public domain, and were thus freely available for anyone to use.

But just as the project was getting up to speed, it almost immediately lost momentum and came to a halt. Like the brilliant dash of a comet receding into darkness, Documerica departed the American stage almost as abruptly as it had arrived. By 1975, photo assignments had essentially dried up. In 1977, the project was officially concluded. And finally in 1981, after a circuitous u-turn through Arizona, the picture collection and existing documents were received by the National Archives back in Washington, where they now rest.

Inspired vision

For any effort like Documerica to take root and survive within the federal bureaucracy, a special set of preconditions has to exist. Government agencies, even new ones like the EPA (only a year old when the project launched), are rarely perceived as hotbeds of innovation. For such a bold initiative to gain critical mass, both a committed promoter and a connected protector are necessary. The earlier FSA documentary project had largely succeeded not only through the inspiration and leadership of a single individual, Roy Stryker, but also through the sustained support of FSA Administrator Rexford Tugwell, and his successors.

Documerica was the beneficiary of a similarly paired dyad. The EPA’s first administrator, William Ruckelshaus, was immediately drawn to the idea, and with White House approval, provided institutional cover and support for it as long as he led that agency. But in making it happen day to day, the project owed its existence almost entirely to the inspired vision and persistent determination of one man, Gifford Hampshire.

Born in the Dust Bowl of western Kansas and raised during the Depression, Hampshire personally experienced living conditions that became the subject of many FSA photographs. Following decorated service on a bomber air crew in the western Pacific during World War II, he studied journalism at the University of Missouri at a time when its photojournalism program, destined to become the preeminent such course of study in America, was just getting started. Among his instructors was Arthur Rothstein, who in the 1930s had been one of the principal FSA photographers.

|

|

| Documerica founder and director Gifford Hampshire (left) at an early exhibition, with the EPA's first administrator, William Ruckelshaus. Photo: Courtesy Gifford Hampshire Family. | Documerica founder and director Gifford Hampshire (right) in 1974, with former FSA Photo Project director Roy Stryker (center) and Arthur Rothstein, a former FSA photographer. Photo: Courtesy Gifford Hampshire Family. |

Hampshire’s professional career ultimately led to Washington D.C., where he served as a picture editor at National Geographic for five years — experience that would later serve him well at Documerica — before taking a public affairs position with the Food and Drug Administration. In 1970, he transferred to the EPAat its creation, and as one of the public affairs leaders on the charter staff, immediately realized the potential to replicate for the environment what the FSA had earlier done with photography for agriculture and rural poverty. With Ruckelshaus’ approval and his commitment to provide the project all necessary support, Documerica was born. “That’s the reason it happened at all,” Hampshire later told UC Berkeley journalism Professor Ken Light, author of Witness in Our Time, a study of documentary photographers. Years later in an unpublished memoir, he added, “As long as I had Bill Ruckelshaus’ support, I was secure.”

Rather than go through the laborious and time-consuming Civil Service procedures for hiring federal employees, Hampshire was able to assign all the project photography to freelancers. His former teacher Arthur Rothstein signed on as an adviser, and Hampshire turned to national professional photography organizations as well as his own connections to recruit his first batch of shooters, who were paid the basic $150 photography day rate of that era, plus expenses.

Michael Philip Manheim, who was embarking on a career in art photography, remembers responding to an invitation circulated to members of the American Society of Magazine (now Media) Photographers to meet Hampshire for lunch at Boston’s Durgin Park restaurant. Boyd Norton, a former nuclear power industry physicist turned nature photographer, answered a similar call in Denver. In San Francisco, Charles O’Rear, a former newspaper photographer who had already completed one assignment for National Geographic, was tapped for Documerica.

In a significant departure from the more hands-on approach Roy Stryker had taken in managing the FSA photographers, Hampshire’s instructions to his first cadre of photographers to go into the field were far more general. He emphasized just two guidelines:

- “First, establish a 1972 baseline of the environmental problems and accomplishments in the geographical area assigned to you.”

- “Second, look for pictures wherever you are, for whatever purpose. Where you see people, there's an environmental element to which they are connected. The great Documerica pictures will show the connection and what it means.”

Rather than give them specific assignments, each was free to cover a subject of their own choosing, just so long as it adhered to EPA program interests. “My philosophy was we’re dealing with intelligent people here, people who are concerned about things,” he later recalled in Ken Light’s Witness in Our Time. “They have the resources, the intellectual resources, to develop it.”

|

|

Former Documerica photographer Michael Philip Manheim back on Neptune Road in April 2010. Photo: Courtesy Michael Philip Manheim.

|

Develop it they did. Manheim was so drawn to use his photographic skills “to contribute to the cause” of environmental protection, that he gladly waived his copyright to the work he produced, a project requirement. “I never did that before, and I would never do it again,” he now says. As a result, the pictures he produced for the challenging task he’d assigned himself — photographing noise pollution and the impact it had on residents in the immediate vicinity of Boston’s Logan International Airport — immediately became public records.

For Norton, whose career switch to nature photography was still a bit financially shaky, Documerica “came along at a very opportune time.” Like Manheim, he was equally committed to benefiting the environment through his work, which later led to his induction as a charter Fellow of the International League of Conservation Photographers in 2005. Norton chose to document ranchers in Montana who were “fighting to keep their land from being strip mined, and to maintain their traditional lifestyle.” Closer to his Denver home, he also covered the first publicly traded solar energy company in America, and admitted to a bit of “insider trading” afterwards, “I bought stock in it, but it went under.”

O’Rear, recommended by an editor at National Geographic, believes he may have done more work than any other photographer in the program, covering a whole range of subjects on the West Coast, and that he was the only project photographer dispatched to Hawaii. He also documented the “healthiest men in America” in Seward County, Nebraska, while work he did on the Lower Colorado River later led to an expanded story in the Geographic, where he worked for the next twenty-five years as a contract photographer.

O’Rear voiced one lament that seemed to be universally shared by all the photographers, “I worked alone.” Other than the initial meetings where they all first gathered to be considered for the project, “We never saw each other again.”

In that way, Documerica was significantly different than its FSA predecessor, whose photographic staffers enjoyed a good deal more collegiality. In contrast, the whole Documerica operation resembled something akin to a bicycle wheel, with a hundred or so spokes, representing the photographers, all linked to the hub, the project headquarters in Washington. In the beginning, “It didn’t require much of a staff,” Hampshire explained to Ken Light in Witness in Our Time, and consisted of “just me and my secretary.” He added, “All I needed was a set-up to handle the film when it came in, and get it processed, and get it into a file.”

The latter proved to be a challenge for a headquarters staff of two, plus an intern or two, the equivalent of a skeleton crew for an operation assigning so many photographers into the field all at once. Norton, who used to call Hampshire from time to time, observed, “Initially, he seemed to suffer from a lack of organization.” Eventually the staff was expanded to include a picture editor.

Tom Powell, who served in that capacity during the mid-1970s, remembers learning that the position had been open for several months before he first reported for work. “I was given a corner office, 16 by 20 feet, with no windows,” he recalls. “I walked into it, and all I could see, floor to ceiling, were yellow boxes,” the characteristic packaging Kodak labs used when processing color transparency film. Powell’s job was to “look at the film, and make a selection that fairly represented what the photographer had shot.”

Two ‘selects’ were kept to go into the Documerica collection from each subject or scene the photographer shot; the rest was returned to the photographer as ‘outtakes.’ Photographers also received a duplicate slide for each original slide of theirs to be retained by the collection. Unfortunately, the quality of these‘dupes’ proved to be far inferior to the quality of the original transparency film they were duplicating, a disparity that continues to have negative ramifications for the Documerica collection to this day.

‘No fire in the belly’

The bulk of the current Documerica collection was photographed between 1972 and 1974. That scale of production was expected to continue, but when an economic recession intervened in 1974, all Federal agency budgets had to be cut back, and Documerica took a big hit.

During the same period, political events in Washington deriving from the Watergate incident were building toward the resignation of President Nixon in August 1974. (Interestingly, the Documerica collection contains virtually no imagery relating to Watergate.) In response to resignations by high-ranking officials, Nixon appointed EPA head William Ruckelshaus to be deputy attorney general at the Justice Department. Six months later, in what became known as the Saturday Night Massacre, Ruckelshaus and Attorney General Elliot Richardson chose resignation rather than carry out Nixon’s order to fire Watergate Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox.

With Documerica’s champion at EPA gone and its budget in tatters, Hampshire was forced to retrench. “Gradually, the guys that resented my doing it in the first place came out of the woodwork, as always happens in government,” he told Ken Light. “One of them wound up being my boss.” Photography assignments slowed to a trickle. “As far as photographers were concerned, it ended in 1976.” Budget constraints even prevented the final 6,000 images selected for the collection from ever being properly catalogued.

In his unpublished personal memoir written about the same time (1997-98), Hampshire was more blunt, “As soon as Bill left EPA, my enemies attacked me and Documerica ... And then my health began to fail.” Following stroke-like symptoms leading up to a heart attack in 1977, he had bypass surgery in 1978.

After his convalescence, Hampshire “went back to work determined not to let events there hurt me any more,” he wrote in his memoir. Instead, he “found an EPA wallowing in a morass of ineffectiveness due to political/industry pressures on a leadership without a clear sense of mission. My superiors cared only for their own security. There was no sense of purpose. No fire-in-the-belly.” Nevertheless, he hung on at the EPA, servicing picture requests as they came in, but fielding no photographers, until he took early retirement in February 1980, having lost hope that a change in presidential administrations would help rejuvenate the project. “Documerica was just a file now,” he lamented in his memoir.

To the warehouse

For the photographers, the demise of Documerica was like receiving a recorded message that a friend’s phone number has been disconnected. “During the shooting, I felt connected to Giff and EPA, but as soon as the project ended and staff was terminated, there became a void,” O’Rear remembered. “There was nobody to talk with and nobody knew where the photos had gone.”

Norton even tried to do something about it. He arranged for Hampshire to meet with Gary Hart of Colorado and Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus, an old friend from his nuclear power industry days in Idaho, in an effort to find solutions to the project’s budgetary problems. “I coordinated all this with Giff and he met personally with Gary and Cece,” Norton says, “but to no avail.”

Documerica’s departure from the EPA is an event somewhat shrouded in mystery. When Hampshire described it to Light in the late 1990s, he stated, “As soon as I was out the door, the National Archives people who had wanted to add Documerica to their still picture collection came to the EPA and asked for it ...EPA agreed ... and it went to the Archives.”

But the collection’s last act at the EPA actually occurred the month before Hampshire retired. Records show it was shipped off — not from Washington, but from a commercial photo lab in New York City — and not to the National Archives as would be expected, but to the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Claiming to be “the largest institution in the world devoted to documenting the history of North American photography,” the CCP houses a number of premiere picture collections, including the work of Ansel Adams. Contributing the Documerica set to this institution would seem a perfect fit, were it not for federal regulations requiring all inactive U.S. Government records and documents to go to the National Archives. Within 16 months, the feds came calling, and the collection was soon on its way back to Washington.

For the next 16 years, the collection was housed in cold storage at an off-site Archives facility in Alexandria, VA, virtually unavailable to the public. Then around 1997, theapproximately 16,000 images that had been catalogued were included in a larger group of materials intended to be scanned into digital files for eventual placement at low resolution in a massive online database called the Archives Research Catalog. Only at this point did the Documerica image collection once again become reasonably accessible, now by computer. Its long disappearing act was about to come to an end.

Awakening

Nearly four decades after Documerica’s launch, Norton harbored dreams of renewing the project he joined at the dawn of his photographic career. At a meeting of the International League of Conservation Photographers in 2009, he broached the idea of a Project Documerica 2.0, sending a proposal to current EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson. It generated no response.

But an official assigned to its Office of External Affairs and Environmental Education in Boston experienced her own epiphany upon encountering the collection for the first time in 2010. Jeanethe Falvey, who managed the EPA’s Flickr photostream, had long had a passion for photography and visual arts. “As soon as I saw it,” she said, “it literally choked me up ... I couldn’t wait to find out more about it.” Aware that the EPA would soon turn 40, she quickly concluded that revisiting these photographs in some manner was “the perfect way to celebrate our 40th anniversary.” She shortly came up with the same idea that Boyd Norton had — go back and re-photograph the same spots now that Documerica did 40 years ago.

The EPA has created a State of the Environment Photo Project that could be dubbed Docuworld, since it invites participants from all over the world, not just the United States, to submit their work, not just the United States. "Environmental issues these days don't know national boundaries," she likes to point out. Part of that project is the Location Challenge, which seeks to have photographers actually re-shoot the same scenes depicted in the original Documerica photographs forty years ago.

The project commenced on Earth Day, 2011 (April 22nd) and will close on or about Earth Day, 2012. “Photos that best illustrate the new ‘after’ view of the same original Documerica ‘before’ photo,” according to an agency statement, “will have a chance to become part of the Earth Day 2012 State of the Environment Exhibit at the U.S. National Archives in Washington, D.C. and travel around the country.”

There are two huge differences, however. EPA will not pay or reimburse for the photos and it asks photographers not to submit any pictures of recognizable people. Falvey is sensitive to the concern that the new rules may severely limit the number of Documerica originals that can be replicated. But she hopes a good number of original Documerica photographers will be willing to participate again, and return to photograph the same scenes that they did 40 years ago.

Falvey can already point to one key success. Manheim has not only agreed to return to Neptune Road in East Boston to again photograph low flying aircraft approaching Logan Airport over a now homeless landscape, but he’s also signed on to judge a student photo contest that the EPA is concurrently sponsoring as a part of its State of the Environment Project.

|

|

| Documerica photographer Michael Philip Manheim shot a 727 airliner flying low over homes on East Boston’s Neptune Road in May 1973 as it approached Logan International Airport. Photo by Michael Philip Manheim, EPA-Documerica / NARA. | Michael Philip Manheim, accompanied by a reporter from NPR’s Living on Earth, returned to Neptune Road in 2010 to shoot the same view from the same spot and same direction as his 1973 picture. Photo: © Michael Philip Manheim. |

“My father would be thrilled that there is a renewal effort,”said Gifford R. Hampshire, the son of the project’s founder. Hampshire, who practices law in Manassas, Va., and his twin sister, Victoria, have sought to keep the project’s memory alive since their father’s death in 2004.

Hampshire considered Documerica the “peak achievement”of his career. But its premature demise was a great disappointment to him. The ironic twist may be that it’s just possible that Project Documerica’s untimely termination was its great saving grace. Had it endured all these years, it might silently have slipped into the background noise of endlessly produced government data that tracks changes in our lives, like the census or the consumer price index. But ending as it did, like the earlier FSA photography, it left a clear picture of our life at a particular time that has not been obstructed by millions more pictures piling up on top of it.

For Documerica to be rediscovered, it first had to be lost. And if it hadn’t ever been lost, it probably never would have been found.

Almost 20 years after leaving Documerica, Hampshire seemed to draw a similar conclusion, according to Light’s Witness in Our Time. “Documentary has no commercial value and no real journalistic value at the time, but if it’s preserved and kept in a public file in the public domain, then maybe it does,” Hampshire said. “Today, if someone wants to understand the environment in the early 1970s, they can find the answer partially in that file — to the extent that we did our job properly. That makes it a baseline of what was happening in America environmentally when the EPA started — those images have meaning only because of their relationship to the time, the place, and the circumstances at a later date.”

Roger Archibald is photo editor of SEJournal.

* From the quarterly newsletter SEJournal, Winter 2011-12. Each new issue of SEJournal is available to members and subscribers only; find subscription information here or learn how to join SEJ. Past issues are archived for the public here.

Advertisement

Advertisement