SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

|

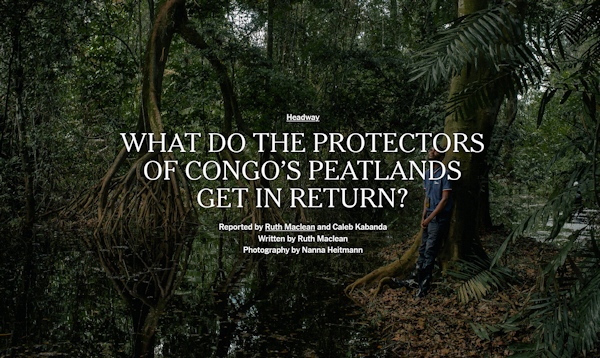

| A screenshot from the first-place winner of the large market feature story prize from the Society of Environmental Journalists’ 22nd Annual Awards for Reporting on the Environment, "What Do the Protectors of Congo's Peatlands Get in Return?" by Ruth Maclean and Caleb Kabanda, with photography by Nanna Heitmann, for The New York Times. |

Inside Story: The Battle To Protect Congo’s Vast Peatlands

One of the world’s largest carbon sinks has long been protected by local communities in the Congo forests. But invading logging operators threaten this invaluable natural resource. New York Times reporter Ruth Maclean and journalist Caleb Kabanda teamed up to craft an award-winning, in-depth story about peatlands, an important element of nature that experts say is critical in the battle against climate change.

Judges with the Society of Environmental Journalists annual awards program were greatly impressed with the story’s richly character-driven, cinematic narrative, its detailed reporting, character portrayals and strong aerial and video components. They awarded it first place for Outstanding Feature Story, Large, in SEJ’s 22nd Annual Awards for Reporting on the Environment.

SEJournal recently asked Maclean and Kabanda about the project by email. Here is the conversation, edited lightly for clarity and brevity.

SEJournal: How did you get your winning story idea?

|

| Ruth Maclean |

Maclean: The Congo Basin peatlands have been on my mind for a while but I had no idea what story I would find when I went there.

Kabanda: I was contacted by Ruth Maclean. She told me that she would like to come to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to report on the peatlands in the Congo Basin forests. She asked if I was available to work with her. I felt very excited because I found the idea and the story great, very interesting and very helpful to the whole planet, and to the whole of humanity. I had already heard about peatlands but didn’t know what they looked like. So, it was a great opportunity to visit the peatlands to witness with my own eyes what they look like and learn more about them. I made some phone calls and learned that no single journalist nor even DRC government officials have ever visited the Congo’s peatlands. Then, I told Ruth that her idea and story were fabulous because we would be the first journalists to report about it and get to witness what peatlands look like.

SEJournal: What was the biggest challenge in reporting the piece and how did you solve that challenge?

Maclean: Logistics and bureaucracy. I solved it with the help of the amazing Caleb Kabanda, my collaborator on the story.

Kabanda: The biggest challenges in reporting the series were getting permissions from the security services (the Congolese national intelligence agency that is the Congolese FBI) and accessibility. The peatlands are located in very remote areas, very far in deep Congo Basin forests, where you need to travel by plane, four-wheel-drive vehicle, speed boat, wooden boat and also travel long hours during the day and sometimes at night on foot under the rain in a deep jungle forest, crossing rivers, falling into mud, getting hurt sometimes by thorns and sometimes being stung by ants, in areas where there is no cellphone reception.

I got media accreditation to enable us to cover the story and I navigated the security services, explaining to them why it is important to inform the whole world about the importance of peatlands and forests to humanity, but also by gaining the trust of local communities, known as peatlands’ protectors, to talk to us, to explain to us what they know about peatlands and also take us to the peatlands. We convinced the local chiefs, along with local communities, that we want to spend much time with them. We want to see how they live and interact with peatlands. We want to learn from them what they know about peatlands. We want to learn what peatlands mean to them, what peatlands mean to the whole of humanity. After talking to them and explaining clearly what we came to do, they were convinced and open to telling us their stories and answering our questions. They allowed us to cover their daily activities in the peatlands, at home and more.

SEJournal: What most surprised you about your reporting?

‘The desire of communities living around

the peatlands to protect them for the world,

despite having almost nothing themselves.’

— Ruth Maclean, on what most

surprised her about her reporting

Maclean: The desire of communities living around the peatlands to protect them for the world, despite having almost nothing themselves.

Kabanda: What personally surprised me is first, to see that the peatlands’ protectors (local communities living in remote forests around the peatlands) are well-informed about the role and the importance of peatlands and forests to the planet and to humanity. They explained to us how the forests and peatlands contribute to fighting against climate change. They showed us how peatlands and forests contribute to their daily living, in terms of feeding and treating their families. Second, I noticed that local communities are willing and managing to protect peatlands and forests but, unfortunately, they are very limited. They regret that polluters continue polluting the world and are demanding the peatlands’ protectors protect the forests and peatlands, but get nothing in return.

SEJournal: How did you decide to tell the story and why?

Maclean: In a long narrative with multimedia elements, because I was working with the incredible photographer Nanna Heitmann, had a brilliant editing team at The New York Times’ Headway, and because I encountered such great characters and was able to witness their struggle to protect the peatlands in person.

SEJournal: Does the issue covered in your story have disproportional impact on people of low income, or people with a particular ethnic or racial background? What efforts, if any, did you make to include perspectives of people who may feel that journalists have left them out of public conversation over the years?

Maclean: The whole story was focused on some of the poorest villages in the world. It was very important to listen to them and try to faithfully represent their perspectives.

SEJournal: What would you do differently now, if anything, in reporting or telling the story and why?

|

| Caleb Kabanda |

Maclean: There are so many angles I would have kept following, if only I had had more time.

SEJournal: What lessons have you learned from your story or project?

Maclean: To focus on people when doing environmental stories.

Kabanda: Peatlands and forests in the Congo Basin are in danger if no alternative measures are taken to protect them. Local communities survive from these peatlands and forests: Their main resources are forests and peatlands; they cut trees from the forests for firewood, making charcoal and planks. Local loggers and mainly international logging companies, conspiring with some corrupt individuals from the Congolese government, are badly and illegally exploiting timbers from the Congo forests. And most of the local communities earn their livings by fishing in peatlands, which poses a small-scale destruction threat to peatlands.

SEJournal: What practical advice would you give to other reporters pursuing similar projects, including any specific techniques or tools you used and could tell us more about?

Maclean: I would encourage other reporters to spend hours with their interviewees if possible and really try to listen.

‘With any obstacles, remain

positive, patient and courageous.’

— Caleb Kabanda

Kabanda: For reporters intending to cover similar projects in the DRC and most of the African countries: Get legal permits/media accreditation for reporting. Get all required permissions, stamps and signatures from government and security services. Be positive in navigating local security services. Be patient in handling all the bureaucracies. Navigate local authorities and local communities to get their trust. Identify the best characters with good knowledge, well-informed about the area or the region. Get to know the customs of the local communities to facilitate good communication. Always remember to assess the security situation of the area of reporting. Work with a local professional fixer or local journalist who is professional in navigating any situation and who has a good array of contacts. With any obstacles, remain positive, patient and courageous.

SEJournal: Could you characterize the resources that went into producing your prizewinning reporting (estimated costs, i.e., legal, travel or other; or estimated hours spent by the team to produce)? Did you receive any grants or fellowships to support it?

Maclean: Two weeks on the ground, several more writing it up, thousands of dollars.

Kabanda: Reporting in DRC is very expensive. Media accreditation and a filming permit are extremely expensive. Plane tickets, car rental, boat rental and hotels are very expensive. Most of the infrastructure is almost dead. There are more bureaucracies and harassment from the security services, which always slows down the reporting.

SEJournal: Is there anything else you would like to share about this story or environmental journalism that wasn’t captured above?

Maclean: The Congo peatlands need and deserve much more attention.

Ruth Maclean is the West Africa bureau chief for The New York Times. Previously, she worked for The Guardian and The Times of London, reporting from Africa, Europe and Latin America for 15 years. She aims to provide nuanced coverage of the 25 countries she covers, with a focus on the people living in them.

Caleb Kabanda is a freelance journalist, camera operator, field producer, professional fixer and first aid responder for international reporters, filmmakers, movie stars and researchers. He is based in Goma in the Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo and has worked with reporters from the BBC, National Geographic, The Washington Post and many others.

[Editor’s Note: View a video interview with Maclean about her prizewinning story below.]

SEJ Awards 2023: Outstanding Feature Story, Large from SEJ: Society of Env. Journalists on Vimeo.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 9, No. 30. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement