SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

|

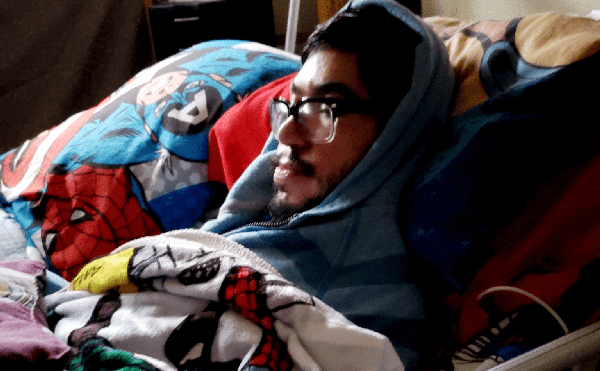

| Ralph Garcia at home in San Antonio, Texas, during a blackout caused by a severe winter storm in 2021. Photo: Courtesy of Ralph Garcia. |

Feature: Disabilities and Disasters — What Questions Should You Be Asking Planners?

By Greg Harman

Earlier this year, eight San Antonio residents sued the city for alleged violations of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, or ADA. The city, it was claimed in a federal lawsuit filed in January, had failed repeatedly to include the needs of people living with disabilities in its disaster planning, resulting in unnecessary physical suffering and psychological trauma during and after the 2021 winter storm that interrupted power to millions around the state for days on end.

“Despite the ADA’s 'clear and comprehensive national mandate for the elimination of discrimination against individuals with disabilities,'” the lawsuit reads, “the City of San Antonio discriminates against people with disabilities by denying equitable opportunities, outcomes, or even consideration in disaster and emergency planning, response, and recovery programs, services, and activities.”

Failure to educate disabled residents

about how to prepare for disasters was

one complaint in the San Antonio suit.

Failure to educate disabled residents about how to prepare for disasters was one complaint. Another was the alleged failure to evacuate residents with disabilities or provide accommodations at shelters for those who were able to get out of their houses.

In researching and writing the story, I spoke with disability rights researchers, attorneys and advocates from around the country, as well as a San Antonio resident living with multiple disabilities who survived the storm.

In addition to helping me understand conditions — both national and local — that preceded the lawsuit, some sources also offered rules of thumb intended to help determine if emergency planners are integrating the needs of people with disabilities.

Their advice may be useful to those interested in examining the state of preparedness in their own communities.

The particular impacts of disaster

I have written frequently over the years on how structural racism and classism in our political and legal systems place inequitable burdens on communities of color and low-income individuals and families. However, researching this story was a reminder of both how late in coming the promises of civil and legal rights have been for people living with disabilities and also how disability studies itself has recently emerged as a field of inquiry.

Laura Stough, professor emerita at Texas A&M University and founder of Project REDD (Research and Evaluation on Disability and Disaster), had been researching disability-related issues for some years before Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005. However, it was only through her volunteer work assisting hurricane victims who fled to Texas that she came to consider the particular impacts of disaster on those living with disabilities.

“I'd never in all my career thought about emergency preparedness when someone with blindness or an intellectual disability experiences a disaster,” Stough told me. “We have put in place our evacuation and preparedness plans very often in ways that are able-body normalized. We think that people can run or climb through windows or crouch underneath a table or hear a siren.”

In her subsequent research, Stough came to understand how a range of particular populations, including mothers, young children, the elderly, veterans and people of color, had received attention denied the disability community.

When the world goes topsy-turvy

Though understudied, the challenges facing those with disabilities during disaster are obvious once the right questions are asked.

“The basic world is not structured for us,” said Dr. Lisa I. Iezzoni, a wheelchair user for 35 years. “When that world is put topsy-turvy so it's not habitable for other people, it's probably even less so for us.”

Iezzoni is based at the Health Policy Research Center at Massachusetts General Hospital and is a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

‘We function differently in the world,

... so if a day is no longer average

because there's a tornado or mudslide

or whatever, it becomes even more complicated.’

— Lisa I. Iezzoni

While her work focuses on discrimination against people with disabilities within the medical community, she effectively summarized the challenges disasters and poor disaster planning represent for those with mobility challenges. “We function differently in the world on an average day, so if a day is no longer average because there's a tornado or mudslide or whatever, it becomes even more complicated,” Iezzoni said.

|

| Health policy researcher Dr. Lisa I. Iezzoni. Photo: Jeffrey Andree. |

Mobility challenges also loom large for Stephanie Duke in her work as disaster resilience coordinator at Disability Rights Texas and a lead attorney in the case against San Antonio.

“Anytime you have power disrupted you're going to have water issues, gas issues and communication issues,” Duke said. “Generally, jurisdictions have plans for food and water distribution. But if you can't get to those distribution sites, guess what? You're not getting them. That's where inclusion comes into the process. For the ones who are homebound or don't have transportation, who can we tap into to make sure everyone is getting those resources?”

As someone who has lived with an invisible disability most of my professional life, I was embarrassed by how little I knew of this civil rights struggle.

The lawsuit, however, did not take me by surprise. I had interviewed Ralph Garcia, a man who lives with disabilities that make him reliant on a variety of home medical devices, over the phone during the 2021 freeze that brought the state within minutes of collapsing the state's power grid.

Questioning disaster planners

So how can journalists judge if their local disaster planners are coordinating with the disability community?

It can be hard to tell by simply reviewing a city or county disaster plan. Oftentimes, local governments adopt templates produced at a state level, disability researcher Stough said.

Rather, it may be instructive to explore how well disaster planners know and understand local residents with disabilities who are within their boundaries. This should become clear with a few well-directed questions.

Stough suggested reporters begin by asking questions like:

- What percentage of people in your area live with disabilities? Drill down. Ask about the percentage of people with particular types of disability (visual, hearing, mobility, etc.) that might require additional support in the case of an emergency.

- Do the planners have the contact information for group homes and other congregate-care living facilities in the community? Does each of these facilities have an emergency plan and have the planners reviewed it with them?

- What are the disability-related organizations in your county, including advocacy groups and nonprofits? Have planners met with them in the development of emergency plans?

- What emergency management organizations, disability-related organizations, nonprofits, faith-based organizations and civic organizations (local, state or national) will provide assistance to people with disabilities in your county in the case of a disaster?

- What are the emergency plans for students with disabilities should an emergency occur during the school day? Have planners reviewed these plans with administrations in school districts in the county?

Policy advances despite legislative inaction

In Texas, we just saw an effort to mandate planning around disability and disaster — Bill HB 2858, authored by Rep. Penny Morales Shaw — fail at the Texas Legislature.

In a session marked by Republican attacks on renewable energy, trans children, local democratic governance and refugee seekers at the border, HB 2858 itself was not unpopular, Morales Shaw’s media rep said. It was just new in concept and didn't get the hearing it needed to advance.

Despite the absence of action by the legislators, there have been small policy advances that make disabled Texas residents safer, said Duke of Disability Rights Texas.

One example has been changes in language at the Texas Health and Human Services Commission that have expanded the definition of backup generators in Medicaid waiver handbooks. The new language allows for battery backup systems in addition to more traditional gas-powered generators, which pose a risk for those on oxygen, for instance.

It's also an improvement that benefits renters.

“If you are renter, gas-powered generators are either going to get stolen off your porch or it's not safe for you to use,” Duke said.

In an encouragement that should ring true for all journalists, Duke said the lack of transparency itself should be a “red flag” for those exploring the intersection of disaster policies and disability.

Emergency planning should always be “public facing,” she said.

As we move into peak hurricane season in the United States, it's a perfect time to ask questions of those leading disaster planning.

SIDEBAR: Superstorm Sandy Suit Found NYC Failed Residents With DisabilitiesIf the City of San Antonio is found in violation of the ADA it will not be because there wasn't a clear legal warning. A very similar suit went to jury trial in 2013 charging New York City and then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg with discriminating against disabled residents in their emergency planning and response. The judge praised New York City emergency responders broadly for their work during Superstorm Sandy but also found they had, indeed, failed residents with disabilities. New York City was found in violation of the ADA in ways that are now being echoed in the San Antonio complaint. In practice, that included:

“At the most basic, shelters were inaccessible,” Joe Rappaport, executive director of the Brooklyn Center for Independence of the Disabled, summarized. “If you were in a wheelchair, you couldn't get in; if you were blind, you couldn't get around.” In spite of a mediated settlement in the New York case, it won't be until another major disaster that the effectiveness of implemented changes becomes clear, Rappaport said. But one thing the lawsuit forced was a level of coordination with the disability community that had not existed previously. |

Greg Harman is the founder and co-editor of Deceleration, an online journal of environmental justice rooted in the South Texas bioregion. He is an independent journalist and former community organizer who has written about environmental health and justice issues since the late 1990s. His work has appeared in places such as The Austin Chronicle, The Guardian, The Dallas Morning News, Indian Country Today, Yes! Magazine, Vice, Houston Press, Texas Observer, among others.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 8, No. 34. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement