SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

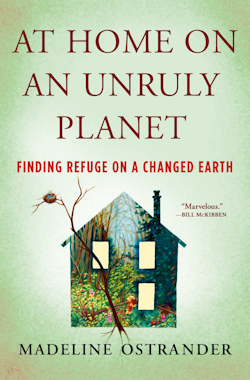

BookShelf: Between the Lines — Author Explores Experience of Living Through Climate Change

For the latest edition of our occasional Q&A series, “Between the Lines,” SEJournal BookShelf Editor Tom Henry interviewed author Madeline Ostrander about her award-winning book, “At Home on an Unruly Planet: Finding Refuge on a Changed Earth.” The book offers accounts of Americans working to protect the places they live, from rural Alaska and urban California to coastal Florida. Ostrander, who lives in Seattle, is currently on a yearlong Knight Science Journalism fellowship at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Mass. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

|

| Author Madeline Ostrander. |

SEJournal: Your book tells the story of climate change through the eyes of people who have had or will potentially have their sense of home disrupted. How did you come up with the idea for that approach and why do you believe it is an effective strategy for storytelling?

Madeline Ostrander: The book started in a few different places. One of those was some reporting I was doing in environmental justice communities, especially in California. The environmental justice movement has for a long time focused on the idea of home as a way to talk about environmental issues. Because when you think about the local scale of environmental problems, you start to notice the kind of disparities that exist, the ways that particularly vulnerable people, people of color and low-income people tend to be burdened more with pollution and with different kinds of environmental impacts than society at large.

And so that lens has been applied to climate justice, as well, and that means that when you talk to folks who are active in environmental justice and climate justice, you get this very local grassroots, grounded, concrete way of thinking about climate change.

Too often, we’ve thought about climate change as a very abstract, global phenomenon. And while it is a global phenomenon, it is already affecting all of us and the places we live. I felt that story about how it will affect us and the places that we live was a really important story that wasn’t being told enough and still isn’t being told enough yet. I felt like it was a way of telling the story that would make people care and that’s why I chose to write the book that way.

Seeking out ‘vital voices’

SEJournal: Of the many people you met in researching this book, how did you choose which ones to focus on?

Ostrander: For any journalist, when you go into a community to report on a story or an issue or a particular question, there are certain people that emerge as you start asking around. There are people who are leading the call, who are the movers and the shakers, and who have some important voices. Or even just some contrary or interesting or especially vital voices in that community. People start referring you to those voices, those individuals again and again. Some of the people in the book emerged in that way.

For instance, Carlene Anders, who led a huge fire recovery effort in north-central Washington state. I found her because she was everywhere, doing all of this impressive work in bringing people together to talk about wildfire recovery and wildfire readiness. She was really an important force behind a lot of conversations about how we respond to climate change.

There are other people I found because I was looking for particular kinds of perspectives. Susan Prichard is a forest ecologist who has also lived through a series of megafires, so she has both this personal experience and this scientific knowledge about how wildfires work. She saw these impacts coming and she’s also lived them, so I thought that perspective was really important to me. I wanted someone who understood it both on a personal and a scientific level.

‘I wanted to find a person, a character,

a protagonist whose life journey could

help the readers and myself reflect

on a particular set of questions.’

There are sections of the book that are narrative storytelling and there are sections of the book that are essays. In some of the essay chapters, I wanted to find a person, a character, a protagonist whose life journey could help the readers and myself reflect on a particular set of questions.

For instance, in one of the sections of the book, I focused on Elinor Ostram, a political scientist who won a Nobel Prize for economics. She did a lot of important, very fascinating research on how we manage shared resources, particularly environmental resources, and how that can be done successfully. To some degree, she debunked the idea of the tragedy of the commons, that there’s no way to share resources collectively without making a big mess of them as humans. In fact, there are lots of examples around the world where people have successfully managed irrigation or pastures or other kinds of shared resources for many generations. I wanted to tell her story as a hopeful set of examples of how we might rethink our response to climate change.

Making people feel less alone

SEJournal: What has surprised you about the response to the book?

Ostrander: I’ve been really pleased with the different ways it has resonated with people. I heard from a scientist who works for a federal agency who said it helped him think through some of his feelings about climate change and some of his climate grief and climate anxiety, and come to terms with it on a personal level, which is hard for a scientist to do because they have to compartmentalize things so much.

I heard recently from someone in Canada who said she felt like she had turned away from the climate crisis altogether, even though she'd studied biology because she wanted to make a difference in environmental issues. She had felt paralyzed and hopeless, and when she read the book she was able to start coming back to her community and find ways to get involved, even in small ways. That is an incredible response to hear from a reader. It allowed them to rethink their own actions. I think that’s what every journalist dreams of hearing. I’ve heard from people that the book made them feel less alone.

What I hoped for with the book was to give people some ideas about climate change on the scale that they could handle. A lot of the ways we talk about climate change are hyper-individualized and reflect our hyper-individualized culture. We talk a lot about carbon footprint. Should we drive or ride a bike? Should we eat a veggie burger or something else? Should you put a garden in your backyard? And some of those things can be joyful and important and lead to cultural change.

‘We’re so hard-wired to want to be

part of a collective effort. The book is

trying to get people to tap into that.’

But if you’re focusing on your individual response, it can in some ways lead to hopelessness because you’re just this one person doing this one thing. When people come together in a community and come up with something — we’re going to develop a community solar project, we’re going to create an urban garden, we’re going to come up with a living shoreline — that's so much more empowering. We’re so hard-wired to want to be part of a collective effort. The book is trying to get people to tap into that, because that is more of a productive and hopeful way to respond to climate change.

SEJournal: There’s no shortage of data about floods, wildfires, hurricanes and other phenomena getting more frequent and more intense. Earth’s climate is warming and more erratic. Annual studies document the billions of dollars of damage that climate-related impacts have on our economy. Yet many people still refuse to accept the science of climate change. Why?

Ostrander: I’ve been spending some time with scholars who study disinformation over human history. The answer to why climate denial exists is complex, but one of the reasons is that there’s been an active and very effective disinformation campaign led by industries that wanted to delay action on climate change. And of course, some wonderful investigative journalist teams at places like Inside Climate News and the Los Angeles Times have helped expose those efforts.

But I think another issue is that people haven’t heard enough stories about how climate change is relevant to them. They don’t always connect the dots between an extreme heat wave or a drought that is happening right in front of them and climate change. They may think that it’s a big contentious political issue but not a local phenomenon.

Some groups, such as EcoAdapt based in Washington state, have had successes holding climate change conversations in conservative communities by drawing attention to the local impacts and the ways that climate will affect people’s livelihoods and places they care about. Those conversations can sometimes get around the political divisiveness and allow people to have productive interactions about solutions.

So that’s a large part of what I also tried to do with the storytelling in my book — communicate that climate change is an issue that is affecting you personally at home — and you have the power to help do something about it.

Considering narrative, distinctive storytelling

SEJournal: What recommendations do you have for would-be book authors? When did you know you were ready to start writing and what challenges did you encounter, in terms of writing technique, so you could offer something distinctive from other climate change books?

|

Ostrander: One of the most significant things I needed to teach myself as I wrote this book was the story structure of a book. A magazine feature might be 3,000 to 10,000 words. The arc of a 3,000- or 4,000-word story is much shorter and condensed than a book chapter or the arc of the narrative that stretches across a book. And, so, I had to change my thinking about how you sustain a story over that period of time. That’s a really important question. There are books that fail to do that and they're not as readable for that reason. Book authors can learn a lot, especially journalists who are trying to be book authors, about studying narrative technique.

I thought about this book for many years, for something like a decade. About four years ago, I started pitching it to literary agents. There have been a lot of big, abstract books about climate change that are a bit gloomy or very gloomy, and books that are policy-driven. There haven’t been enough books that are narrative that people can relate to that tell stories about climate change that people can grab ahold of. So they were excited that I was finding a way to do that and that I had my own particular voice.

That’s one thing to think about when you are writing a book: What are you doing to tell a story that’s a bit distinct? They talked me down from — oh, I don’t know — 15 stories I wanted to put into the book to just four. That was helpful feedback from my literary agents. One of the strengths of the book is that it allows you to feel your feelings about climate change and it does that by exposing you to these particular places where people are facing the impacts and you get to care about those places.

Emotion, fact in service of story

SEJournal: How did you balance emotion and fact while writing this book? People seem to want both, but it must be a delicate balance, right?

Ostrander: I didn’t set out to write a book about the emotions of climate change. And yet a lot of people — when they read the book — tell me it feels like an emotional appeal or it feels like a book that is really dwelling on the emotions of climate change. I think the reason for that is that I chose to tell stories about people who are being personally affected and as soon as you get into that territory of personal and something as meaningful and powerful as home you get into emotional territory.

‘It’s not so much that I try

to balance emotion and fact.

It's that I try to tell a good story.’

I didn’t spend a lot of time thinking about where I am being emotional and where I am being fact-based. I thought about the story, what’s in service of the story. So, for the arc of any story, there are places where you need to supply facts and to help it rise to something bigger than just what’s happening in the moment. There are places where I pull back in the book and I really tell the story of climate change and the science of how we understand things. It’s not so much that I try to balance emotion and fact. It’s that I try to tell a good story. And that’s probably why the book’s so successful. It appeals to people’s emotions. It’s just letting you see into the worlds that people are living and reflect on how your own experiences might relate to those.

SEJournal: How have you seen the climate change issue evolve over the years you have been reporting on it? How did living in Seattle help shape your vision?

Ostrander: I’ve been reporting on climate change for something like 15 years. There was still a lot of coverage devoted to whether climate change was real or who didn’t think it was real. Even then we were seeing a lot of the impacts of climate change showing up. Hurricane Katrina was a wake-up call for us about what a climate disaster could look like and the kinds of incredible disparities and unfairness and misery it could cause. It was very shocking. At this point, we’re seeing more and more impacts of climate change at home. Now we can finally have a discussion about what we can do about it.

Issues faith communities care about

SEJournal: There are some religious ideas about creation care and stewardship that seem to dovetail with the ideas of home that you explore in your book. Did that fit into your thinking?

Ostrander: The book itself is not overtly spiritual. I never mention spirituality except when some of my protagonists are part of a religious community. But, serendipitously, the book addresses issues that faith communities often care about, such as taking care of the most vulnerable people and even larger issues like what it means to be human during a time of crisis. I think it resonated with some religious communities because of that.

‘People don’t always realize

the important connections between

faith communities and climate response.’

I would also say that people don’t always realize the important connections between faith communities and climate response. While there are some conservative Christian communities that reject climate science, there also has also been a big effort from a group of religious organizations to respond to climate change. I don’t think that’s gotten enough attention. For instance, Interfaith Power and Light has organized church communities all around the country, both to reduce its own emissions and also to get involved in political activism on climate change.

In the rollout of the book, I’ve tried to connect with some of these communities. For instance, I’ve done some events with a Unitarian church, and I did two book talks with Greg Epstein, who is a humanist chaplain at Harvard and MIT. He commented that I was ministering to my readers, the way that a chaplain might. That’s an unusual role for a journalist, but I also like the idea that I am helping readers process their feelings and find meaning and a sense of purpose through an often frightening and difficult set of issues

SEJournal: When you hear the phrase “climate refugee,“ what image does that give you? Do you really believe people will be seeking refuge in more climate-friendly parts of the world in the future — at least those who can — or are they more likely to exhaust every effort at adapting to their particular circumstances to remain in a place that is familiar to them and in sync with their cultural upbringing?

Ostrander: There are already people moving because of climate impacts. There are people moving away from the coasts, there are people moving away from wildfire-prone areas because they can’t get insurance or because they want to, because they are tired of the risks or tired of the smoke. There’s plenty of evidence documenting this.

To some extent, the phrase “climate refugee” suggests someone who has been forced out of a place and, like a lot of refugees, doesn’t have a lot of resources or capacity to find any place. We’re going to have a lot of those people. We already have a lot of those people. It’s not very well tracked. We don’t have a lot of data on climate migration. But people are already moving and will continue to move. They will move sometimes by choice and sometimes by necessity.

One of the messages of the book is that our ability to respond to these kinds of impacts, our ability to move, our ability to adapt, our ability to come up with solutions and be safe is connected to our ability to find community and to have people to support us. That’s a neglected aspect of the response to climate change.

Madeline Ostrander is a science journalist and writer whose work has appeared in the NewYorker.com, The Nation, Sierra magazine, PBS’s NOVA Next, Slate and numerous other outlets. Her reporting on climate change and environmental justice has taken her to locations such as the Alaskan Arctic and the Australian outback. She’s received grants, fellowships and residencies from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, Artist Trust, the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, the Fund for Investigative Journalism, the Jack Straw Cultural Center, the Mesa Refuge, Hedgebrook and Edith Cowan University in Australia. She is the former senior editor of YES! magazine and holds a master’s degree in environmental science from the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 8, No. 43. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement