SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

Between the Lines: Subramanian on ‘Writing the Book You Can’t Not Write’

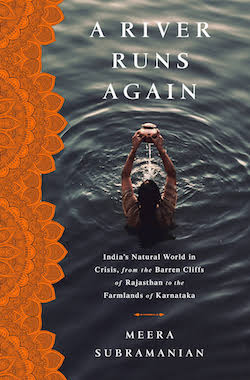

For the latest installment of SEJournal’s author Q & A, “Between the Lines,” Meera Subramanian talks to book editor Tom Henry about the research and writing process behind her debut, “A River Runs Again: India’s Natural World in Crisis,” a 2016 Orion Book Award finalist that travels from the barren cliffs of Rajasthan to the farmlands of Karnataka.

SEJournal: What inspired you to write “A River Runs Again?”

Meera Subramanian: I have visited India all my life to see my father’s family and couldn’t help but observe how things were done there compared to my home in the United States. I’d be older with each trip, viewing with a new perspective, but India was changing, too, and when the country opened up its economy in the 1990s, that change ramped up to a frantic pace.

But who was getting left behind as the IT boom swept South Asia? Where was this country that is now poised to become the most populous nation on Earth heading in terms of development? What were they doing right and what were they doing wrong in a place where a growing population was colliding with limited natural resources, where everyone wants to satisfy their basic needs — and then some?

But this wasn’t just describing India; it was the state of the entire world. I decided to start with India, a place I could view with the fresh eyes of an outsider but also with a touch of insider knowledge.

|

| Author Meera Subramanian. |

SEJournal: What challenges did you face as a writer in your book by shedding light on the downward plight of vultures, a largely misunderstood bird that often doesn’t evoke much sympathy?

Subramanian: That part of the story fascinated me from the very first time I learned about it, and still does. How does the catastrophic loss of an unloved bird reveal hidden connections between human health, ecological systems and even religious beliefs? But the toughest part was grappling with the heartbreak of studying extinction up close. Of experiencing the loss that conservation biologists feel turned tangible when we found a sick vulture, and I held this wild, dying maligned creature in my arms, and thought: this is what the loss of a species looks like. It’s not some vague, faraway fact. It is something living, vanishing. The good news is that the bird survived, which gives me hope that the species can too!

SEJournal: What did you learn about yourself while researching and writing this book? How did it help you grow as a writer and a person? How did it strengthen your bond with your ancestral homeland?

Subramanian: I learned what I was capable of as a writer, in terms of focus and attention. It felt like being in the middle of this elaborate 3D puzzle in which I had more pieces than would ever fit and I had to figure out which ones belonged, and where. I scrawled “Joy & Delight” on my computer to remind me that those two elusive states should be present even when everything felt completely untenable. I also learned how incredibly patient loved ones around me can be. I can’t say I was very pleasant to be around during the thick of the writing process.

I definitely deepened my connection with India during my research, experiencing so many parts of the country that were so far from the familiar familial circles of South India. I studied Hindi, hired my cousin’s daughter as an assistant for part of my travels, crashed on relatives’ couches whenever possible and kind of enjoyed baffling unsuspecting Indians who couldn’t figure out where I was from.

SEJournal: Why did you believe it was important to weave together stories of ancient traditions of India with modern technology instead of just focusing on the here and now?

Subramanian: Maybe it was a reflection of my own personal biases. For a long period in my 20s and early 30s, I lived a pretty pared down existence on a farm in rural Oregon and, during those years, I would visit India and glean how they lived good lives in simple ways. There could be a delicious abundant multi-course meal prepared efficiently in a pressure cooker on a two-burner stove.

“How do we create a new model of

development for the 21st century that allows

human abundance without ecological devastation?”

I thought America had a lot it could learn from India. But India was also suffering from a widespread lack of access to basic means of survival such as healthy food, clean water and energy for the majority of its population. It seemed the answer was partly in modern technological advancements, but I knew people in both hemispheres who also felt those same technologies were failing them and they were definitely failing many ecosystems. So where was the balance between old and new? I went looking for the answers. How do we create a new model of development for the 21st century that allows human abundance without ecological devastation? Could India lead the way?

SEJournal: Your book has been lauded for its beautiful prose and storytelling technique, for offering perspective through the eyes of characters such as the Rainman of Rajasthan, who’s credited for helping a dry valley get back some of the water it desperately needed. Why were such anecdotes important and how do they help you connect with readers?

Subramanian: I have the deepest abiding faith in the power of stories. There has to be solid reporting and research and science to underpin it, but the reality is we understand our worlds through the narratives we live. Sometimes they match the known science, sometimes they stand at stark odds with it and sometimes they hinder us in the worst of ways. But sometimes, someone else’s stories can crack us open in the best of ways. It’s all a writer can hope for is that one of those stories sticks.

SEJournal: Though your book was written with an optimistic tone, you also tackled some tough issues, such as a woman in an impoverished area boldly educating young girls about their bodies as sexual violence became more prevalent. What parallels did you find between social problems and how people treat the natural world?

Subramanian: It’s not just parallels, but an elaborate spider’s web of connection. I framed the structure of the book around the five elements — earth, water, fire, air and ether — but they are all inextricably intertwined, just as the natural world and our human lives are. I’m convinced that the dichotomy of jobs versus the environment, for example, is utterly false. India is losing 5 to 6 percent of its GDP to environmental degradation. Develop, yes, but increasingly there are options for how to do that without paying the environmental costs that cripple true sustainable growth that can weather the long-term.

“I have the deepest abiding faith in the power of stories.

... The reality is we understand our worlds

through the narratives we live.”

SEJournal: What convinced you to embrace humans as you wrote this story instead of just the science? Was it any more difficult in India, with its huge population, hot climate, crowded streets and ancient history, than it would be in, say, America?

Subramanian: It’s interesting you ask because I’m currently working on a series of stories from the heartland of America, and I find more parallels than differences in the struggles individual people are facing, even if the scale varies. Getting around in America is easier in some ways, but more expensive and isolating. We need more trains and rickshaws here. And I worked in India long enough that I was able to plan reporting trips to avoid the worst of heat and monsoon downpours accordingly, neither of which is avoidable here anymore.

It’s true that India’s sheer mass of humanity can be overwhelming, and the stories of horror are always the ones to get out, but my experience on the ground was meeting people who were generous with their time and their stories, who welcomed me in and always offered a cup of tea, which as a caffeine addict, always made me grateful. That rarely happens in my American interviews.

|

SEJournal: This was your first book. What advice would you give to SEJ members who think they might have a book inside of them?

Subramanian: Write the book that you can’t not write. It’s a tremendous amount of work, not just the research and writing but the energy required to get it out into the world as a new author.

And you also have to keep yourself solvent in the process. I didn’t get an advance that would keep me afloat for the three years it took to write [my book]. You need to be deeply engaged with the material, and want to stay with it for a long time, since even after the book is done, you will (hopefully) still be asked to speak about it and write about it and think about it, so write about something that makes you curious and always leads to more questions.

SEJournal: Did you have trouble getting your book published and what did you learn about marketing and other things from the business side of writing that journalists often don’t think about?

Subramanian: I had a failed book proposal that I labored over for years about the resurrection of peregrine falcons, so I learned a lot about what not to do. Because “A River Runs Again” was a book about India, I took a circuitous route. After mulling over the idea, I wrote the proposal quickly and then pitched it to Indian publishers. They bit, and then my agent helped me hone the proposal for American publishers, who bought it a year later.

I encourage a five-pronged approach: book deal(s), freelance pieces along the way that draw on the book research, fellowships and grants (shout out to SEJ’s Fund for Environmental Journalism and a Fulbright fellowship), residencies and awards, and speaking engagements after publication. Seek all of it, but don’t get attached to any of it. In the words of the wise Dan Fagin, who served as my SEJ mentor as I was working on “A River Runs Again,” as soon as the book is done, start thinking about your next project. Onward!

Meera Subramanian is a freelance writer based in Cape Cod, Mass. She recently completed a Knight Science Journalism fellowship at MIT and is also a former Fulbright-Nehru senior research fellow. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, the New Yorker and other publications, and has been anthologized in Best American Science and Nature Writing and multiple editions of Best Women’s Travel Writing. Subramanian won first place in SEJ’s 2012 feature writing category. She is recipient of an SEJ diversity fellowship, and is currently writing a series of stories for InsideClimate News about how Americans are reacting to climate change in their respective communities.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 2, No. 35. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement