Journalists are eligible for free email subscriptions to SEJournal, including TipSheet, WatchDog (on access issues) and more.

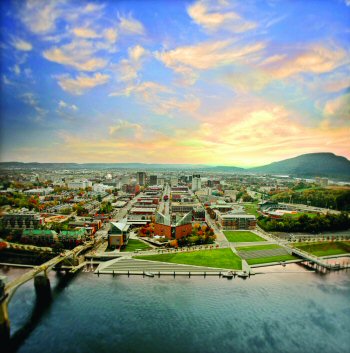

Chattanooga, Tennessee

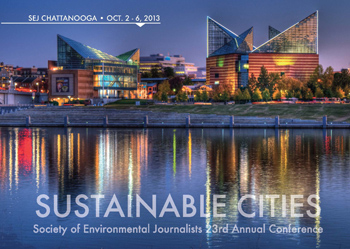

The Evolution of

Sustainability

| Agenda | Registration | Lodging/Travel | Exhibits/Receptions | Environmental News | About Chattanooga |

- Official City Website for Chattanooga, Tennessee

- Chattanooga Area Convention and Visitors Bureau (CVB): Visitor guide, what to do, where to eat, deals and coupons, events calendar, more.

- Chattanooga Times Free Press

- "Explore by bike: Wind through trails in around Chattanooga with mountains lining the horizon," Chattanooga Times Free Press, August 19, 2013, by Beth Burger.

- "Chattanooga's Makeover Secret: A River Runs Through It," National Journal, August 19, 2013, by Nancy Cook.

- Chattanooga weather

- Free Electric Shuttle for getting around town. SHUTTLE SCHEDULE

Chattanooga's environmental history from our host, the Chattanooga Times Free Press:

More than 12,000 years ago, Native Americans first settled Chattanooga because they saw the potential of a lush and biodiverse place where the mountains came to a point and ringed a valley that headed into the grand canyon of what they called the Tanase River.

In the late 1700s, settlers from Germany and the British Isles discovered the same amazing wonderland, married into the local tribes and gradually set up shop, opening river ports and goods stores, businesses and foundries to service farms, river traffic and expanding railroads.

By the time the Civil War unfolded across the land, Chattanooga was a coveted southern railroad hub that became the Union Army’s gateway to overpower the Confederacy.

Just as the city was moving beyond the Civil War, the Tennessee River flooded in 1867. Stunned by waters reaching 30 feet above the river’s normal banks, townspeople quietly and steadily began to raise their street levels by 3 to 15 feet.

Three more floods in 50 years strengthened the efforts, and in time, about a 40-block area of the city rose by about a story. First floors became basements. Second floors became front doors, and soils from old foundries and rail yards moved all over town.

Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), created by Congress in 1933, built dams and brought electricity.

By then, Chattanooga was known as the "Dynamo of Dixie", and it inspired the 1941 Glenn Miller big-band swing song “Chattanooga Choo Choo.”

Two world wars came and went.

During each, industrial work here grew. But in a time before there was any pollution regulation, so did dirty air and murky streams.

Growing up industrial

A company known as Tennessee Products opened in 1913 to burn coal to make coke, which was burned in foundries to melt iron and make steel for the machinery of those wars.

During war, the plant was operated by the U.S. Department of Defense. It ran incessantly for three shifts, producing more by-product coal tar than could be sold for asphalt and roofing shingles.

The nasty black sludge had to go somewhere, so it was ditched — literally ditched — to Chattanooga Creek, a stream that began as a pristine trickle in North Georgia and flowed for 24 miles before it reached the city’s industrial corridor. Beyond the industries, the creek flowed five or six more miles to the Tennessee River near the foot of Lookout Mountain.

Across town in a community known as Bonny Oaks, an explosives factory sprawled over 600 acres where TNT was made.

Boys delivering morning papers to city residents left white tracks on the black-dusted sidewalks where the night’s foundry production ash had fallen. Car finishes lasted no time, and nylon stockings seemed to melt hanging on outdoor clotheslines. Morning sun had a hard time penetrating the gray-brown haze that sat in the bowl of Chattanooga between the mountains.

Then in 1969, shortly after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency began using its new pollution standards to measure air quality, Chattanoogans were shocked one evening when Walter Cronkite told the world that Chattanooga was the nation’s dirtiest city.

Waking to change

Chattanooga and Hamilton governments formed an air pollution bureau to be the regulatory arm for the state and EPA.

TVA — scouting water quality — and the new Clean Water Act began bringing similar awareness to rein in some polluters of water.

In the 1970s Chattanooga Creek was posted against swimming or wading or fishing. What the signs didn’t say was that some settled pools of quicksand-like coal tar were eight feet deep and E. coli levels were extremely high when heavy rains forced the city’s decades-old combined sewer storm-water lines to pour straight to the creek and the Tennessee River.

But Chattanooga’s stepped-up regulatory efforts likely wouldn’t have been enough without the help of simple economics.

When the Vietnam War ended, the government stopped TNT production at the Volunteer Army Ammunition Plant.

A few years later, Chattanooga Coke and Chemical shuttered its doors.

For Chattanooga, the worst air and water pollution had ceased.

Now a new challenge loomed. The next milestone would be recovery of its water systems and thousands of acres of polluted land — not to mention finding ways to replace lost jobs.

The real turn-around began in the late 1980s, the 1990s and the past decade.

The Tennessee Aquarium reawakened Chattanooga’s interest in the river and in its scenery.

Children of the city’s old manufacturers became big givers — and big environmental champions.

As manufacturing shrank — here as well as everywhere else in the country — leaders began looking for new jobs, and preferably cleaner ones.

|

| Photo courtesy Chattanooga Area CVB. Click to enlarge. |

With the Aquarium came greenways — lots of them.

And Chattanooga’s then-mayor Bob Corker, looking to higher office in Washington, pushed through a new Waterfront plan further transforming Chattanooga’s public face as an embracer of its past and new future.

Work began in earnest to reclaim VAAP, Chattanooga Coke and Chemical, Velsicol, Wheland — and now U.S. Pipe.

The first real fruit of effort was Volkswagen’s announcement that Chattanooga’s "intangibles" made the come-back city its choice for a new plant site.

Not only did VW pick Chattanooga, the automaker built the world’s first platinum LEED car manufacturing plant, with every conceivable energy saver and water saver.

The plant’s president in 2009 announced that VW came here because of the city’s can-do attitude and environmental awareness. The plant, which employs about 2,000 people, opened in May 2011.

The city also has attracted a windmill-making company, and a solar panels plant is under construction a few miles away.

This year, VW completed Tennessee’s largest solar farm to supply 12 percent — yes 12 percent — of the electricity needed for the robotics-heavy manufacturing plant.

- The Chattanooga Public Library has 41 archived photographs in the Local History set of its Flickr Photostream.

Advertisement

Advertisement